Introduction

As you already know, Django is a Python web framework. And like most modern framework, Django supports the MVC pattern. First let's see what is the Model-View-Controller (MVC) pattern, and then we will look at Django’s specificity for the Model-View-Template (MVT) pattern.

MVC Pattern

When talking about applications that provides UI (web or desktop), we usually talk about MVC architecture. And as the name suggests, MVC pattern is based on three components: Model, View, and Controller. Check our MVC tutorial here to know more.

DJANGO MVC - MVT Pattern

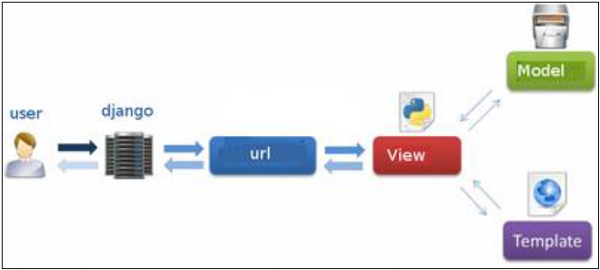

The Model-View-Template (MVT) is slightly different from MVC. In fact the main difference between the two patterns is that Django itself takes care of the Controller part (Software Code that controls the interactions between the Model and View), leaving us with the template. The template is a HTML file mixed with Django Template Language (DTL).

The following diagram illustrates how each of the components of the MVT pattern interacts with each other to serve a user request −

The developer provides the Model, the view and the template then just maps it to a URL and Django does the magic to serve it to the user.

Environment

Django development environment consists of installing and setting up Python, Django, and a Database System. Since Django deals with web application, it's worth mentioning that you would need a web server setup as well.

Step 1 – Installing Python

Django is written in 100% pure Python code, so you'll need to install Python on your system. Latest Django version requires Python 2.6.5 or higher

If you're on one of the latest Linux or Mac OS X distribution, you probably already have Python installed. You can verify it by typing python command at a command prompt. If you see something like this, then Python is installed.

$ python Python 2.7.5 (default, Jun 17 2014, 18:11:42) [GCC 4.8.2 20140120 (Red Hat 4.8.2-16)] on linux2

Otherwise, you can download and install the latest version of Python from the link http://www.python.org/download.

Step 2 - Installing Django

Installing Django is very easy, but the steps required for its installation depends on your operating system. Since Python is a platform-independent language, Django has one package that works everywhere regardless of your operating system.

You can download the latest version of Django from the link http://www.djangoproject.com/download.

UNIX/Linux and Mac OS X Installation

You have two ways of installing Django if you are running Linux or Mac OS system −

-

You can use the package manager of your OS, or use easy_install or pip if installed.

-

Install it manually using the official archive you downloaded before.

We will cover the second option as the first one depends on your OS distribution. If you have decided to follow the first option, just be careful about the version of Django you are installing.

Let's say you got your archive from the link above, it should be something like Django-x.xx.tar.gz:

Extract and install.

$ tar xzvf Django-x.xx.tar.gz $ cd Django-x.xx $ sudo python setup.py install

You can test your installation by running this command −

$ django-admin.py --version

If you see the current version of Django printed on the screen, then everything is set.

Note − For some version of Django it will be django-admin the ".py" is removed.

Windows Installation

We assume you have your Django archive and python installed on your computer.

First, PATH verification.

On some version of windows (windows 7) you might need to make sure the Path system variable has the path the following C:\Python34\;C:\Python34\Lib\site-packages\django\bin\ in it, of course depending on your Python version.

Then, extract and install Django.

c:\>cd c:\Django-x.xx

Next, install Django by running the following command for which you will need administrative privileges in windows shell "cmd" −

c:\Django-x.xx>python setup.py install

To test your installation, open a command prompt and type the following command −

c:\>python -c "import django; print(django.get_version())"

If you see the current version of Django printed on screen, then everything is set.

OR

Launch a "cmd" prompt and type python then −

c:\> python >>> import django >>> django.VERSION

Step 3 – Database Setup

Django supports several major database engines and you can set up any of them based on your comfort.

- MySQL (http://www.mysql.com/)

- PostgreSQL (http://www.postgresql.org/)

- SQLite 3 (http://www.sqlite.org/)

- Oracle (http://www.oracle.com/)

- MongoDb (https://django-mongodb-engine.readthedocs.org)

- GoogleAppEngine Datastore (https://cloud.google.com/appengine/articles/django-nonrel)

You can refer to respective documentation to installing and configuring a database of your choice.

Note − Number 5 and 6 are NoSQL databases.

Step 4 – Web Server

Django comes with a lightweight web server for developing and testing applications. This server is pre-configured to work with Django, and more importantly, it restarts whenever you modify the code.

However, Django does support Apache and other popular web servers such as Lighttpd. We will discuss both the approaches in coming chapters while working with different examples.

Creating A Project

Now that we have installed Django, let's start using it. In Django, every web app you want to create is called a project; and a project is a sum of applications. An application is a set of code files relying on the MVT pattern. As example let's say we want to build a website, the website is our project and, the forum, news, contact engine are applications. This structure makes it easier to move an application between projects since every application is independent.

Create a Project

Whether you are on Windows or Linux, just get a terminal or a cmd prompt and navigate to the place you want your project to be created, then use this code −

$ django-admin startproject myproject

This will create a "myproject" folder with the following structure −

myproject/

manage.py

myproject/

__init__.py

settings.py

urls.py

wsgi.py

The Project Structure

The “myproject” folder is just your project container, it actually contains two elements −

-

manage.py − This file is kind of your project local django-admin for interacting with your project via command line (start the development server, sync db...). To get a full list of command accessible via manage.py you can use the code −

$ python manage.py help

-

The “myproject” subfolder − This folder is the actual python package of your project. It contains four files −

-

__init__.py − Just for python, treat this folder as package.

-

settings.py − As the name indicates, your project settings.

-

urls.py − All links of your project and the function to call. A kind of ToC of your project.

-

wsgi.py − If you need to deploy your project over WSGI.

-

Setting Up Your Project

Your project is set up in the subfolder myproject/settings.py. Following are some important options you might need to set −

DEBUG = True

This option lets you set if your project is in debug mode or not. Debug mode lets you get more information about your project's error. Never set it to ‘True’ for a live project. However, this has to be set to ‘True’ if you want the Django light server to serve static files. Do it only in the development mode.

DATABASES = { 'default': { 'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.sqlite3', 'NAME': 'database.sql', 'USER': '', 'PASSWORD': '', 'HOST': '', 'PORT': '', } }

Database is set in the ‘Database’ dictionary. The example above is for SQLite engine. As stated earlier, Django also supports −

- MySQL (django.db.backends.mysql)

- PostGreSQL (django.db.backends.postgresql_psycopg2)

- Oracle (django.db.backends.oracle) and NoSQL DB

- MongoDB (django_mongodb_engine)

Before setting any new engine, make sure you have the correct db driver installed.

You can also set others options like: TIME_ZONE, LANGUAGE_CODE, TEMPLATE…

Now that your project is created and configured make sure it's working −

$ python manage.py runserver

You will get something like the following on running the above code −

Validating models... 0 errors found September 03, 2015 - 11:41:50 Django version 1.6.11, using settings 'myproject.settings' Starting development server at http://127.0.0.1:8000/ Quit the server with CONTROL-C.

App Lifecycle

A project is a sum of many applications. Every application has an objective and can be reused into another project, like the contact form on a website can be an application, and can be reused for others. See it as a module of your project.

Create an Application

We assume you are in your project folder. In our main “myproject” folder, the same folder then manage.py −

$ python manage.py startapp myapp

You just created myapp application and like project, Django create a “myapp” folder with the application structure −

myapp/ __init__.py admin.py models.py tests.py views.py

-

__init__.py − Just to make sure python handles this folder as a package.

-

admin.py − This file helps you make the app modifiable in the admin interface.

-

models.py − This is where all the application models are stored.

-

tests.py − This is where your unit tests are.

-

views.py − This is where your application views are.

Get the Project to Know About Your Application

At this stage we have our "myapp" application, now we need to register it with our Django project "myproject". To do so, update INSTALLED_APPS tuple in the settings.py file of your project (add your app name) −

INSTALLED_APPS = ( 'django.contrib.admin', 'django.contrib.auth', 'django.contrib.contenttypes', 'django.contrib.sessions', 'django.contrib.messages', 'django.contrib.staticfiles', 'myapp', )

Admin Interface

Django provides a ready-to-use user interface for administrative activities. We all know how an admin interface is important for a web project. Django automatically generates admin UI based on your project models.

Starting the Admin Interface

The Admin interface depends on the django.countrib module. To have it working you need to make sure some modules are imported in the INSTALLED_APPS and MIDDLEWARE_CLASSES tuples of the myproject/settings.py file.

For INSTALLED_APPS make sure you have −

INSTALLED_APPS = ( 'django.contrib.admin', 'django.contrib.auth', 'django.contrib.contenttypes', 'django.contrib.sessions', 'django.contrib.messages', 'django.contrib.staticfiles', 'myapp', )

For MIDDLEWARE_CLASSES −

MIDDLEWARE_CLASSES = ( 'django.contrib.sessions.middleware.SessionMiddleware', 'django.middleware.common.CommonMiddleware', 'django.middleware.csrf.CsrfViewMiddleware', 'django.contrib.auth.middleware.AuthenticationMiddleware', 'django.contrib.messages.middleware.MessageMiddleware', 'django.middleware.clickjacking.XFrameOptionsMiddleware', )

Before launching your server, to access your Admin Interface, you need to initiate the database −

$ python manage.py migrate

syncdb will create necessary tables or collections depending on your db type, necessary for the admin interface to run. Even if you don't have a superuser, you will be prompted to create one.

If you already have a superuser or have forgotten it, you can always create one using the following code −

$ python manage.py createsuperuser

Now to start the Admin Interface, we need to make sure we have configured a URL for our admin interface. Open the myproject/url.py and you should have something like −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, include, url from django.contrib import admin admin.autodiscover() urlpatterns = patterns('', # Examples: # url(r'^$', 'myproject.views.home', name = 'home'), # url(r'^blog/', include('blog.urls')), url(r'^admin/', include(admin.site.urls)), )

Now just run the server.

$ python manage.py runserver

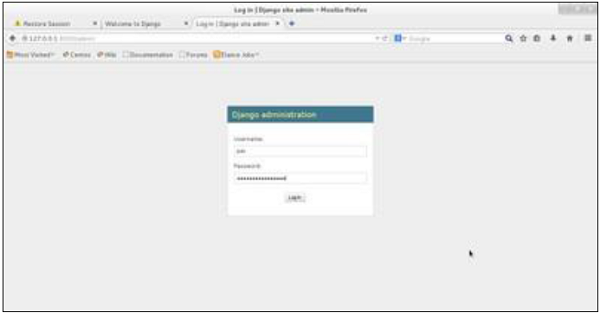

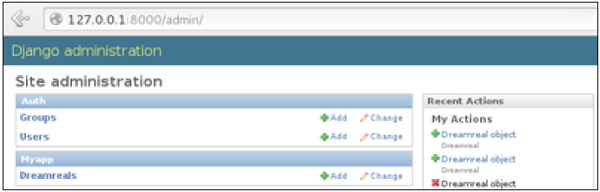

And your admin interface is accessible at: http://127.0.0.1:8000/admin/

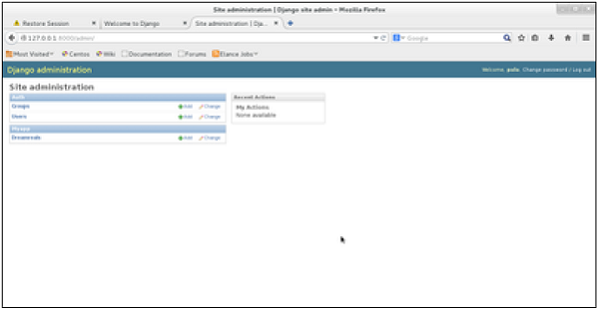

Once connected with your superuser account, you will see the following screen −

That interface will let you administrate Django groups and users, and all registered models in your app. The interface gives you the ability to do at least the "CRUD" (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operations on your models.

Creating Views

A view function, or “view” for short, is simply a Python function that takes a web request and returns a web response. This response can be the HTML contents of a Web page, or a redirect, or a 404 error, or an XML document, or an image, etc. Example: You use view to create web pages, note that you need to associate a view to a URL to see it as a web page.

In Django, views have to be created in the app views.py file.

Simple View

We will create a simple view in myapp to say "welcome to my app!"

See the following view −

from django.http import HttpResponse def hello(request): text = """<h1>welcome to my app !</h1>""" return HttpResponse(text)

In this view, we use HttpResponse to render the HTML (as you have probably noticed we have the HTML hard coded in the view). To see this view as a page we just need to map it to a URL (this will be discussed in an upcoming chapter).

We used HttpResponse to render the HTML in the view before. This is not the best way to render pages. Django supports the MVT pattern so to make the precedent view, Django - MVT like, we will need −

A template: myapp/templates/hello.html

And now our view will look like −

from django.shortcuts import render def hello(request): return render(request, "myapp/template/hello.html", {})

Views can also accept parameters −

from django.http import HttpResponse def hello(request, number): text = "<h1>welcome to my app number %s!</h1>"% number return HttpResponse(text)

When linked to a URL, the page will display the number passed as a parameter. Note that the parameters will be passed via the URL (discussed in the next chapter).

URL Mapping

Now that we have a working view as explained in the previous chapters. We want to access that view via a URL. Django has his own way for URL mapping and it's done by editing your project url.py file (myproject/url.py). The url.py file looks like −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, include, url from django.contrib import admin admin.autodiscover() urlpatterns = patterns('', #Examples #url(r'^$', 'myproject.view.home', name = 'home'), #url(r'^blog/', include('blog.urls')), url(r'^admin', include(admin.site.urls)), )

When a user makes a request for a page on your web app, Django controller takes over to look for the corresponding view via the url.py file, and then return the HTML response or a 404 not found error, if not found. In url.py, the most important thing is the "urlpatterns" tuple. It’s where you define the mapping between URLs and views. A mapping is a tuple in URL patterns like −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, include, url from django.contrib import admin admin.autodiscover() urlpatterns = patterns('', #Examples #url(r'^$', 'myproject.view.home', name = 'home'), #url(r'^blog/', include('blog.urls')), url(r'^admin', include(admin.site.urls)), url(r'^hello/', 'myapp.views.hello', name = 'hello'), )

The marked line maps the URL "/home" to the hello view created in myapp/view.py file. As you can see above a mapping is composed of three elements −

-

The pattern − A regexp matching the URL you want to be resolved and map. Everything that can work with the python 're' module is eligible for the pattern (useful when you want to pass parameters via url).

-

The python path to the view − Same as when you are importing a module.

-

The name − In order to perform URL reversing, you’ll need to use named URL patterns as done in the examples above. Once done, just start the server to access your view via :http://127.0.0.1/hello

Organizing Your URLs

So far, we have created the URLs in “myprojects/url.py” file, however as stated earlier about Django and creating an app, the best point was to be able to reuse applications in different projects. You can easily see what the problem is, if you are saving all your URLs in the “projecturl.py” file. So best practice is to create an “url.py” per application and to include it in our main projects url.py file (we included admin URLs for admin interface before).

How is it Done?

We need to create an url.py file in myapp using the following code −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, include, url urlpatterns = patterns('', url(r'^hello/', 'myapp.views.hello', name = 'hello'),)

Then myproject/url.py will change to the following −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, include, url from django.contrib import admin admin.autodiscover() urlpatterns = patterns('', #Examples #url(r'^$', 'myproject.view.home', name = 'home'), #url(r'^blog/', include('blog.urls')), url(r'^admin', include(admin.site.urls)), url(r'^myapp/', include('myapp.urls')), )

We have included all URLs from myapp application. The home.html that was accessed through “/hello” is now “/myapp/hello” which is a better and more understandable structure for the web app.

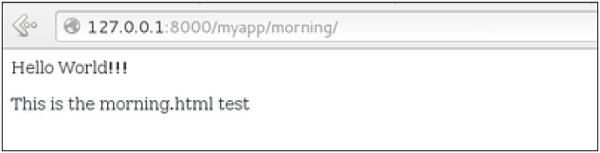

Now let's imagine we have another view in myapp “morning” and we want to map it in myapp/url.py, we will then change our myapp/url.py to −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, include, url urlpatterns = patterns('', url(r'^hello/', 'myapp.views.hello', name = 'hello'), url(r'^morning/', 'myapp.views.morning', name = 'morning'), )

This can be re-factored to −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, include, url urlpatterns = patterns('myapp.views', url(r'^hello/', 'hello', name = 'hello'), url(r'^morning/', 'morning', name = 'morning'),)

As you can see, we now use the first element of our urlpatterns tuple. This can be useful when you want to change your app name.

Sending Parameters to Views

We now know how to map URL, how to organize them, now let us see how to send parameters to views. A classic sample is the article example (you want to access an article via “/articles/article_id”).

Passing parameters is done by capturing them with the regexp in the URL pattern. If we have a view like the following one in “myapp/view.py”

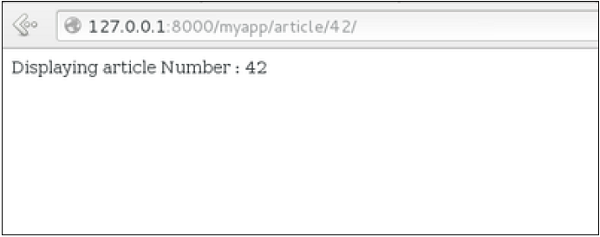

from django.shortcuts import render from django.http import HttpResponse def hello(request): return render(request, "hello.html", {}) def viewArticle(request, articleId): text = "Displaying article Number : %s"%articleId return HttpResponse(text)

We want to map it in myapp/url.py so we can access it via “/myapp/article/articleId”, we need the following in “myapp/url.py” −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, include, url urlpatterns = patterns('myapp.views', url(r'^hello/', 'hello', name = 'hello'), url(r'^morning/', 'morning', name = 'morning'), url(r'^article/(\d+)/', 'viewArticle', name = 'article'),)

When Django will see the url: “/myapp/article/42” it will pass the parameters '42' to the viewArticle view, and in your browser you should get the following result −

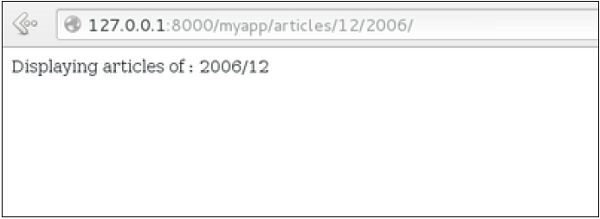

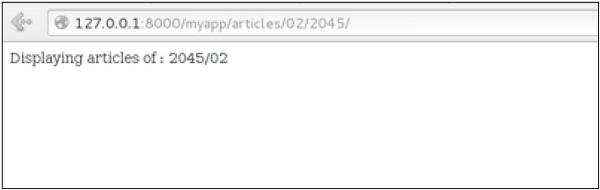

Note that the order of parameters is important here. Suppose we want the list of articles of a month of a year, let's add a viewArticles view. Our view.py becomes −

from django.shortcuts import render from django.http import HttpResponse def hello(request): return render(request, "hello.html", {}) def viewArticle(request, articleId): text = "Displaying article Number : %s"%articleId return HttpResponse(text) def viewArticle(request, month, year): text = "Displaying articles of : %s/%s"%(year, month) return HttpResponse(text)

The corresponding url.py file will look like −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, include, url urlpatterns = patterns('myapp.views', url(r'^hello/', 'hello', name = 'hello'), url(r'^morning/', 'morning', name = 'morning'), url(r'^article/(\d+)/', 'viewArticle', name = 'article'), url(r'^articles/(\d{2})/(\d{4})', 'viewArticles', name = 'articles'),)

Now when you go to “/myapp/articles/12/2006/” you will get 'Displaying articles of: 2006/12' but if you reverse the parameters you won’t get the same result.

To avoid that, it is possible to link a URL parameter to the view parameter. For that, our url.py will become −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, include, url urlpatterns = patterns('myapp.views', url(r'^hello/', 'hello', name = 'hello'), url(r'^morning/', 'morning', name = 'morning'), url(r'^article/(\d+)/', 'viewArticle', name = 'article'), url(r'^articles/(?P\d{2})/(?P\d{4})', 'viewArticles', name = 'articles'),

Template System

Django makes it possible to separate python and HTML, the python goes in views and HTML goes in templates. To link the two, Django relies on the render function and the Django Template language.

The Render Function

This function takes three parameters −

-

Request − The initial request.

-

The path to the template − This is the path relative to the TEMPLATE_DIRS option in the project settings.py variables.

-

Dictionary of parameters − A dictionary that contains all variables needed in the template. This variable can be created or you can use locals() to pass all local variable declared in the view.

Django Template Language (DTL)

Django’s template engine offers a mini-language to define the user-facing layer of the application.

Displaying Variables

A variable looks like this: {{variable}}. The template replaces the variable by the variable sent by the view in the third parameter of the render function. Let's change our hello.html to display today’s date −

hello.html

<html> <body> Hello World!!!<p>Today is {{today}}</p> </body> </html>

Then our view will change to −

def hello(request): today = datetime.datetime.now().date() return render(request, "hello.html", {"today" : today})

We will now get the following output after accessing the URL/myapp/hello −

Hello World!!! Today is Sept. 11, 2015

As you have probably noticed, if the variable is not a string, Django will use the __str__ method to display it; and with the same principle you can access an object attribute just like you do it in Python. For example: if we wanted to display the date year, my variable would be: {{today.year}}.

Filters

They help you modify variables at display time. Filters structure looks like the following: {{var|filters}}.

Some examples −

-

{{string|truncatewords:80}} − This filter will truncate the string, so you will see only the first 80 words.

-

{{string|lower}} − Converts the string to lowercase.

-

{{string|escape|linebreaks}} − Escapes string contents, then converts line breaks to tags.

You can also set the default for a variable.

Tags

Tags lets you perform the following operations: if condition, for loop, template inheritance and more.

Tag if

Just like in Python you can use if, else and elif in your template −

<html> <body> Hello World!!!<p>Today is {{today}}</p> We are {% if today.day == 1 %} the first day of month. {% elif today.day == 30 %} the last day of month. {% else %} I don't know. {%endif%} </body> </html>

In this new template, depending on the date of the day, the template will render a certain value.

Tag for

Just like 'if', we have the 'for' tag, that works exactly like in Python. Let's change our hello view to transmit a list to our template −

def hello(request): today = datetime.datetime.now().date() daysOfWeek = ['Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thu', 'Fri', 'Sat', 'Sun'] return render(request, "hello.html", {"today" : today, "days_of_week" : daysOfWeek})

The template to display that list using {{ for }} −

<html> <body> Hello World!!!<p>Today is {{today}}</p> We are {% if today.day == 1 %} the first day of month. {% elif today.day == 30 %} the last day of month. {% else %} I don't know. {%endif%} <p> {% for day in days_of_week %} {{day}} </p> {% endfor %} </body> </html>

And we should get something like −

Hello World!!! Today is Sept. 11, 2015 We are I don't know. Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun

Block and Extend Tags

A template system cannot be complete without template inheritance. Meaning when you are designing your templates, you should have a main template with holes that the child's template will fill according to his own need, like a page might need a special css for the selected tab.

Let’s change the hello.html template to inherit from a main_template.html.

main_template.html

<html> <head> <title> {% block title %}Page Title{% endblock %} </title> </head> <body> {% block content %} Body content {% endblock %} </body> </html>

hello.html

{% extends "main_template.html" %} {% block title %}My Hello Page{% endblock %} {% block content %} Hello World!!!<p>Today is {{today}}</p> We are {% if today.day == 1 %} the first day of month. {% elif today.day == 30 %} the last day of month. {% else %} I don't know. {%endif%} <p> {% for day in days_of_week %} {{day}} </p> {% endfor %} {% endblock %}

In the above example, on calling /myapp/hello we will still get the same result as before but now we rely on extends and block to refactor our code −

In the main_template.html we define blocks using the tag block. The title block will contain the page title and the content block will have the page main content. In home.html we use extends to inherit from the main_template.html then we fill the block define above (content and title).

Comment Tag

The comment tag helps to define comments into templates, not HTML comments, they won’t appear in HTML page. It can be useful for documentation or just commenting a line of code.

Models

A model is a class that represents table or collection in our DB, and where every attribute of the class is a field of the table or collection. Models are defined in the app/models.py (in our example: myapp/models.py)

Creating a Model

Following is a Dreamreal model created as an example −

from django.db import models class Dreamreal(models.Model): website = models.CharField(max_length = 50) mail = models.CharField(max_length = 50) name = models.CharField(max_length = 50) phonenumber = models.IntegerField() class Meta: db_table = "dreamreal"

Every model inherits from django.db.models.Model.

Our class has 4 attributes (3 CharField and 1 Integer), those will be the table fields.

The Meta class with the db_table attribute lets us define the actual table or collection name. Django names the table or collection automatically: myapp_modelName. This class will let you force the name of the table to what you like.

There is more field's type in django.db.models, you can learn more about them on https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.5/ref/models/fields/#field-types

After creating your model, you will need Django to generate the actual database −

$python manage.py syncdb

Manipulating Data (CRUD)

Let's create a "crudops" view to see how we can do CRUD operations on models. Our myapp/views.py will then look like −

myapp/views.py

from myapp.models import Dreamreal from django.http import HttpResponse def crudops(request): #Creating an entry dreamreal = Dreamreal( website = "www.polo.com", mail = "sorex@polo.com", name = "sorex", phonenumber = "002376970" ) dreamreal.save() #Read ALL entries objects = Dreamreal.objects.all() res ='Printing all Dreamreal entries in the DB : <br>' for elt in objects: res += elt.name+"<br>" #Read a specific entry: sorex = Dreamreal.objects.get(name = "sorex") res += 'Printing One entry <br>' res += sorex.name #Delete an entry res += '<br> Deleting an entry <br>' sorex.delete() #Update dreamreal = Dreamreal( website = "www.polo.com", mail = "sorex@polo.com", name = "sorex", phonenumber = "002376970" ) dreamreal.save() res += 'Updating entry<br>' dreamreal = Dreamreal.objects.get(name = 'sorex') dreamreal.name = 'thierry' dreamreal.save() return HttpResponse(res)

Other Data Manipulation

Let's explore other manipulations we can do on Models. Note that the CRUD operations were done on instances of our model, now we will be working directly with the class representing our model.

Let's create a 'datamanipulation' view in myapp/views.py

from myapp.models import Dreamreal from django.http import HttpResponse def datamanipulation(request): res = '' #Filtering data: qs = Dreamreal.objects.filter(name = "paul") res += "Found : %s results<br>"%len(qs) #Ordering results qs = Dreamreal.objects.order_by("name") for elt in qs: res += elt.name + '<br>' return HttpResponse(res)

Linking Models

Django ORM offers 3 ways to link models −

One of the first case we will see here is the one-to-many relationships. As you can see in the above example, Dreamreal company can have multiple online websites. Defining that relation is done by using django.db.models.ForeignKey −

myapp/models.py

from django.db import models class Dreamreal(models.Model): website = models.CharField(max_length = 50) mail = models.CharField(max_length = 50) name = models.CharField(max_length = 50) phonenumber = models.IntegerField() online = models.ForeignKey('Online', default = 1) class Meta: db_table = "dreamreal" class Online(models.Model): domain = models.CharField(max_length = 30) class Meta: db_table = "online"

As you can see in our updated myapp/models.py, we added the online model and linked it to our Dreamreal model.

Let's check how all of this is working via manage.py shell −

First let’s create some companies (Dreamreal entries) for testing in our Django shell −

$python manage.py shell >>> from myapp.models import Dreamreal, Online >>> dr1 = Dreamreal() >>> dr1.website = 'company1.com' >>> dr1.name = 'company1' >>> dr1.mail = 'contact@company1' >>> dr1.phonenumber = '12345' >>> dr1.save() >>> dr2 = Dreamreal() >>> dr1.website = 'company2.com' >>> dr2.website = 'company2.com' >>> dr2.name = 'company2' >>> dr2.mail = 'contact@company2' >>> dr2.phonenumber = '56789' >>> dr2.save()

Now some hosted domains −

>>> on1 = Online() >>> on1.company = dr1 >>> on1.domain = "site1.com" >>> on2 = Online() >>> on2.company = dr1 >>> on2.domain = "site2.com" >>> on3 = Online() >>> on3.domain = "site3.com" >>> dr2 = Dreamreal.objects.all()[2] >>> on3.company = dr2 >>> on1.save() >>> on2.save() >>> on3.save()

Accessing attribute of the hosting company (Dreamreal entry) from an online domain is simple −

>>> on1.company.name

And if we want to know all the online domain hosted by a Company in Dreamreal we will use the code −

>>> dr1.online_set.all()

To get a QuerySet, note that all manipulating method we have seen before (filter, all, exclude, order_by....)

You can also access the linked model attributes for filtering operations, let's say you want to get all online domains where the Dreamreal name contains 'company' −

>>> Online.objects.filter(company__name__contains = 'company'

Note − That kind of query is just supported for SQL DB. It won’t work for non-relational DB where joins doesn’t exist and there are two '_'.

But that's not the only way to link models, you also have OneToOneField, a link that guarantees that the relation between two objects is unique. If we used the OneToOneField in our example above, that would mean for every Dreamreal entry only one Online entry is possible and in the other way to.

And the last one, the ManyToManyField for (n-n) relation between tables. Note, those are relevant for SQL based DB.

Page Redirection

Page redirection is needed for many reasons in web application. You might want to redirect a user to another page when a specific action occurs, or basically in case of error. For example, when a user logs in to your website, he is often redirected either to the main home page or to his personal dashboard. In Django, redirection is accomplished using the 'redirect' method.

The 'redirect' method takes as argument: The URL you want to be redirected to as string A view's name.

The myapp/views looks like the following so far −

def hello(request): today = datetime.datetime.now().date() daysOfWeek = ['Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thu', 'Fri', 'Sat', 'Sun'] return render(request, "hello.html", {"today" : today, "days_of_week" : daysOfWeek}) def viewArticle(request, articleId): """ A view that display an article based on his ID""" text = "Displaying article Number : %s" %articleId return HttpResponse(text) def viewArticles(request, year, month): text = "Displaying articles of : %s/%s"%(year, month) return HttpResponse(text)

Let's change the hello view to redirect to djangoproject.com and our viewArticle to redirect to our internal '/myapp/articles'. To do so the myapp/view.py will change to −

from django.shortcuts import render, redirect from django.http import HttpResponse import datetime # Create your views here. def hello(request): today = datetime.datetime.now().date() daysOfWeek = ['Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thu', 'Fri', 'Sat', 'Sun'] return redirect("https://www.djangoproject.com") def viewArticle(request, articleId): """ A view that display an article based on his ID""" text = "Displaying article Number : %s" %articleId return redirect(viewArticles, year = "2045", month = "02") def viewArticles(request, year, month): text = "Displaying articles of : %s/%s"%(year, month) return HttpResponse(text)

In the above example, first we imported redirect from django.shortcuts and for redirection to the Django official website we just pass the full URL to the 'redirect' method as string, and for the second example (the viewArticle view) the 'redirect' method takes the view name and his parameters as arguments.

Accessing /myapp/hello, will give you the following screen −

And accessing /myapp/article/42, will give you the following screen −

It is also possible to specify whether the 'redirect' is temporary or permanent by adding permanent = True parameter. The user will see no difference, but these are details that search engines take into account when ranking of your website.

Also remember that 'name' parameter we defined in our url.py while mapping the URLs −

url(r'^articles/(?P\d{2})/(?P\d{4})/', 'viewArticles', name = 'articles'),

That name (here article) can be used as argument for the 'redirect' method, then our viewArticle redirection can be changed from −

def viewArticle(request, articleId): """ A view that display an article based on his ID""" text = "Displaying article Number : %s" %articleId return redirect(viewArticles, year = "2045", month = "02")

To −

def viewArticle(request, articleId): """ A view that display an article based on his ID""" text = "Displaying article Number : %s" %articleId return redirect(articles, year = "2045", month = "02")

Note − There is also a function to generate URLs; it is used in the same way as redirect; the 'reverse' method (django.core.urlresolvers.reverse). This function does not return a HttpResponseRedirect object, but simply a string containing the URL to the view compiled with any passed argument.

Sending E-mail

Django comes with a ready and easy-to-use light engine to send e-mail. Similar to Python you just need an import of smtplib. In Django you just need to import django.core.mail. To start sending e-mail, edit your project settings.py file and set the following options −

-

EMAIL_HOST − smtp server.

-

EMAIL_HOST_USER − Login credential for the smtp server.

-

EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD − Password credential for the smtp server.

-

EMAIL_PORT − smtp server port.

-

EMAIL_USE_TLS or _SSL − True if secure connection.

Sending a Simple E-mail

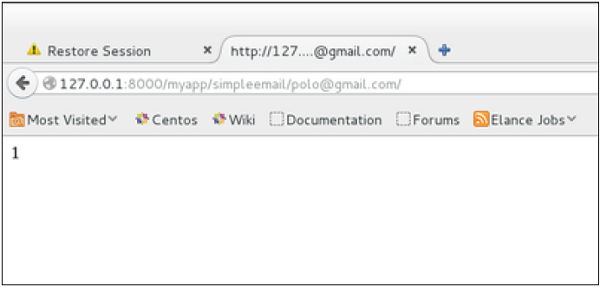

Let's create a "sendSimpleEmail" view to send a simple e-mail.

from django.core.mail import send_mail from django.http import HttpResponse def sendSimpleEmail(request,emailto): res = send_mail("hello paul", "comment tu vas?", "paul@polo.com", [emailto]) return HttpResponse('%s'%res)

Here is the details of the parameters of send_mail −

-

subject − E-mail subject.

-

message − E-mail body.

-

from_email − E-mail from.

-

recipient_list − List of receivers’ e-mail address.

-

fail_silently − Bool, if false send_mail will raise an exception in case of error.

-

auth_user − User login if not set in settings.py.

-

auth_password − User password if not set in settings.py.

-

connection − E-mail backend.

-

html_message − (new in Django 1.7) if present, the e-mail will be multipart/alternative.

Let's create a URL to access our view −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, url urlpatterns = paterns('myapp.views', url(r'^simpleemail/(?P<emailto> [\w.%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Za-z]{2,4})/', 'sendSimpleEmail' , name = 'sendSimpleEmail'),)

So when accessing /myapp/simpleemail/polo@gmail.com, you will get the following page −

Sending Multiple Mails with send_mass_mail

The method returns the number of messages successfully delivered. This is same as send_mail but takes an extra parameter; datatuple, our sendMassEmail view will then be −

from django.core.mail import send_mass_mail from django.http import HttpResponse def sendMassEmail(request,emailto): msg1 = ('subject 1', 'message 1', 'polo@polo.com', [emailto1]) msg2 = ('subject 2', 'message 2', 'polo@polo.com', [emailto2]) res = send_mass_mail((msg1, msg2), fail_silently = False) return HttpResponse('%s'%res)

Let's create a URL to access our view −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, url urlpatterns = paterns('myapp.views', url(r'^massEmail/(?P<emailto1> [\w.%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Za-z]{2,4})/(?P<emailto2> [\w.%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Za-z]{2,4})', 'sendMassEmail' , name = 'sendMassEmail'),)

When accessing /myapp/massemail/polo@gmail.com/sorex@gmail.com/, we get −

send_mass_mail parameters details are −

-

datatuples − A tuple where each element is like (subject, message, from_email, recipient_list).

-

fail_silently − Bool, if false send_mail will raise an exception in case of error.

-

auth_user − User login if not set in settings.py.

-

auth_password − User password if not set in settings.py.

-

connection − E-mail backend.

As you can see in the above image, two messages were sent successfully.

Note − In this example we are using Python smtp debuggingserver, that you can launch using −

$python -m smtpd -n -c DebuggingServer localhost:1025

This means all your sent e-mails will be printed on stdout, and the dummy server is running on localhost:1025.

Sending e-mails to admins and managers using mail_admins and mail_managers methods

These methods send e-mails to site administrators as defined in the ADMINS option of the settings.py file, and to site managers as defined in MANAGERS option of the settings.py file. Let's assume our ADMINS and MANAGERS options look like −

ADMINS = (('polo', 'polo@polo.com'),)

MANAGERS = (('popoli', 'popoli@polo.com'),)

from django.core.mail import mail_admins from django.http import HttpResponse def sendAdminsEmail(request): res = mail_admins('my subject', 'site is going down.') return HttpResponse('%s'%res)

The above code will send an e-mail to every admin defined in the ADMINS section.

from django.core.mail import mail_managers from django.http import HttpResponse def sendManagersEmail(request): res = mail_managers('my subject 2', 'Change date on the site.') return HttpResponse('%s'%res)

The above code will send an e-mail to every manager defined in the MANAGERS section.

Parameters details −

-

Subject − E-mail subject.

-

message − E-mail body.

-

fail_silently − Bool, if false send_mail will raise an exception in case of error.

-

connection − E-mail backend.

-

html_message − (new in Django 1.7) if present, the e-mail will be multipart/alternative.

Sending HTML E-mail

Sending HTML message in Django >= 1.7 is as easy as −

from django.core.mail import send_mail from django.http import HttpResponse res = send_mail("hello paul", "comment tu vas?", "paul@polo.com", ["polo@gmail.com"], html_message=")

This will produce a multipart/alternative e-mail.

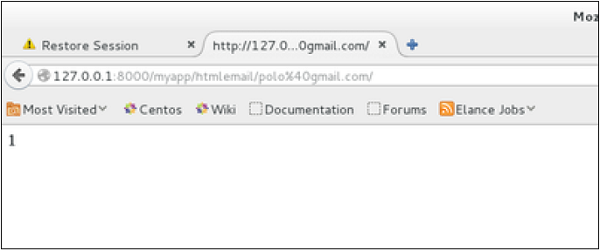

But for Django < 1.7 sending HTML messages is done via the django.core.mail.EmailMessage class then calling 'send' on the object −

Let's create a "sendHTMLEmail" view to send an HTML e-mail.

from django.core.mail import EmailMessage from django.http import HttpResponse def sendHTMLEmail(request , emailto): html_content = "<strong>Comment tu vas?</strong>" email = EmailMessage("my subject", html_content, "paul@polo.com", [emailto]) email.content_subtype = "html" res = email.send() return HttpResponse('%s'%res)

Parameters details for the EmailMessage class creation −

-

Subject − E-mail subject.

-

message − E-mail body in HTML.

-

from_email − E-mail from.

-

to − List of receivers’ e-mail address.

-

bcc − List of “Bcc” receivers’ e-mail address.

-

connection − E-mail backend.

Let's create a URL to access our view −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, url urlpatterns = paterns('myapp.views', url(r'^htmlemail/(?P<emailto> [\w.%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Za-z]{2,4})/', 'sendHTMLEmail' , name = 'sendHTMLEmail'),)

When accessing /myapp/htmlemail/polo@gmail.com, we get −

Sending E-mail with Attachment

This is done by using the 'attach' method on the EmailMessage object.

A view to send an e-mail with attachment will be −

from django.core.mail import EmailMessage from django.http import HttpResponse def sendEmailWithAttach(request, emailto): html_content = "Comment tu vas?" email = EmailMessage("my subject", html_content, "paul@polo.com", emailto]) email.content_subtype = "html" fd = open('manage.py', 'r') email.attach('manage.py', fd.read(), 'text/plain') res = email.send() return HttpResponse('%s'%res)

Details on attach arguments −

-

filename − The name of the file to attach.

-

content − The content of the file to attach.

-

mimetype − The attachment's content mime type.

content − The content of the file to attach.

mimetype − The attachment's content mime type.

Generic Views

In some cases, writing views, as we have seen earlier is really heavy. Imagine you need a static page or a listing page. Django offers an easy way to set those simple views that is called generic views.

Unlike classic views, generic views are classes not functions. Django offers a set of classes for generic views in django.views.generic, and every generic view is one of those classes or a class that inherits from one of them.

There are 10+ generic classes −

>>> import django.views.generic >>> dir(django.views.generic) ['ArchiveIndexView', 'CreateView', 'DateDetailView', 'DayArchiveView', 'DeleteView', 'DetailView', 'FormView', 'GenericViewError', 'ListView', 'MonthArchiveView', 'RedirectView', 'TemplateView', 'TodayArchiveView', 'UpdateView', 'View', 'WeekArchiveView', 'YearArchiveView', '__builtins__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__name__', '__package__', '__path__', 'base', 'dates', 'detail', 'edit', 'list']

This you can use for your generic view. Let's look at some example to see how it works.

Static Pages

Let's publish a static page from the “static.html” template.

Our static.html −

<html> <body> This is a static page!!! </body> </html>

If we did that the way we learned before, we would have to change the myapp/views.pyto be −

from django.shortcuts import render def static(request): return render(request, 'static.html', {})

and myapp/urls.py to be −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, url urlpatterns = patterns("myapp.views", url(r'^static/', 'static', name = 'static'),)

The best way is to use generic views. For that, our myapp/views.py will become −

from django.views.generic import TemplateView class StaticView(TemplateView): template_name = "static.html"

And our myapp/urls.py we will be −

from myapp.views import StaticView from django.conf.urls import patterns urlpatterns = patterns("myapp.views", (r'^static/$', StaticView.as_view()),)

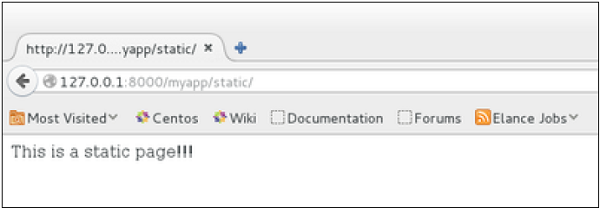

When accessing /myapp/static you get −

For the same result we can also, do the following −

- No change in the views.py

- Change the url.py file to be −

from django.views.generic import TemplateView from django.conf.urls import patterns, url urlpatterns = patterns("myapp.views", url(r'^static/',TemplateView.as_view(template_name = 'static.html')),)

As you can see, you just need to change the url.py file in the second method.

List and Display Data from DB

We are going to list all entries in our Dreamreal model. Doing so is made easy by using the ListView generic view class. Edit the url.py file and update it as −

from django.views.generic import ListView from django.conf.urls import patterns, url urlpatterns = patterns( "myapp.views", url(r'^dreamreals/', ListView.as_view(model = Dreamreal, template_name = "dreamreal_list.html")), )

Important to note at this point is that the variable pass by the generic view to the template is object_list. If you want to name it yourself, you will need to add a context_object_name argument to the as_view method. Then the url.py will become −

from django.views.generic import ListView from django.conf.urls import patterns, url urlpatterns = patterns("myapp.views", url(r'^dreamreals/', ListView.as_view( template_name = "dreamreal_list.html")), model = Dreamreal, context_object_name = ”dreamreals_objects” ,)

The associated template will then be −

{% extends "main_template.html" %} {% block content %} Dreamreals:<p> {% for dr in object_list %} {{dr.name}}</p> {% endfor %} {% endblock %}

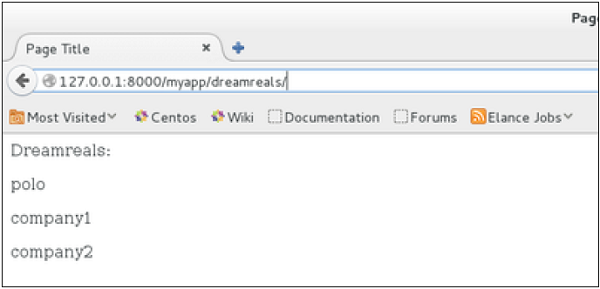

Accessing /myapp/dreamreals/ will produce the following page −

Form Processing

Creating forms in Django, is really similar to creating a model. Here again, we just need to inherit from Django class and the class attributes will be the form fields. Let's add a forms.py file in myapp folder to contain our app forms. We will create a login form.

myapp/forms.py

#-*- coding: utf-8 -*- from django import forms class LoginForm(forms.Form): user = forms.CharField(max_length = 100) password = forms.CharField(widget = forms.PasswordInput())

As seen above, the field type can take "widget" argument for html rendering; in our case, we want the password to be hidden, not displayed. Many others widget are present in Django: DateInput for dates, CheckboxInput for checkboxes, etc.

Using Form in a View

There are two kinds of HTTP requests, GET and POST. In Django, the request object passed as parameter to your view has an attribute called "method" where the type of the request is set, and all data passed via POST can be accessed via the request.POST dictionary.

Let's create a login view in our myapp/views.py −

#-*- coding: utf-8 -*- from myapp.forms import LoginForm def login(request): username = "not logged in" if request.method == "POST": #Get the posted form MyLoginForm = LoginForm(request.POST) if MyLoginForm.is_valid(): username = MyLoginForm.cleaned_data['username'] else: MyLoginForm = Loginform() return render(request, 'loggedin.html', {"username" : username})

The view will display the result of the login form posted through the loggedin.html. To test it, we will first need the login form template. Let's call it login.html.

<html> <body> <form name = "form" action = "{% url "myapp.views.login" %}" method = "POST" >{% csrf_token %} <div style = "max-width:470px;"> <center> <input type = "text" style = "margin-left:20%;" placeholder = "Identifiant" name = "username" /> </center> </div> <br> <div style = "max-width:470px;"> <center> <input type = "password" style = "margin-left:20%;" placeholder = "password" name = "password" /> </center> </div> <br> <div style = "max-width:470px;"> <center> <button style = "border:0px; background-color:#4285F4; margin-top:8%; height:35px; width:80%;margin-left:19%;" type = "submit" value = "Login" > <strong>Login</strong> </button> </center> </div> </form> </body> </html>

The template will display a login form and post the result to our login view above. You have probably noticed the tag in the template, which is just to prevent Cross-site Request Forgery (CSRF) attack on your site.

{% csrf_token %}

Once we have the login template, we need the loggedin.html template that will be rendered after form treatment.

<html> <body> You are : <strong>{{username}}</strong> </body> </html>

Now, we just need our pair of URLs to get started: myapp/urls.py

from django.conf.urls import patterns, url from django.views.generic import TemplateView urlpatterns = patterns('myapp.views', url(r'^connection/',TemplateView.as_view(template_name = 'login.html')), url(r'^login/', 'login', name = 'login'))

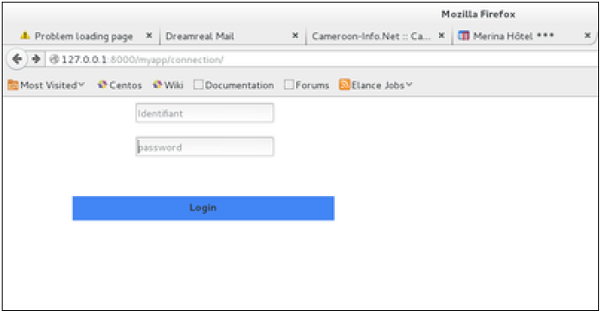

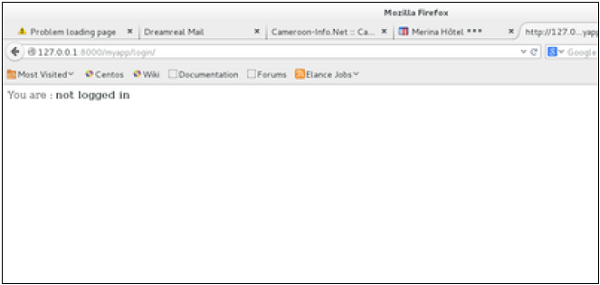

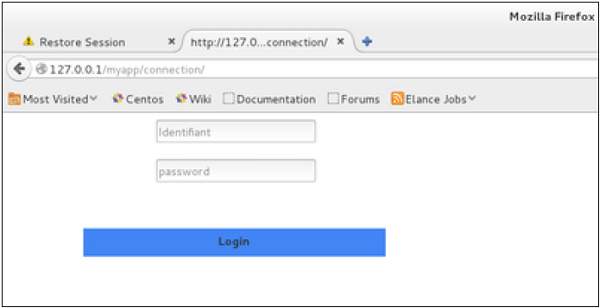

When accessing "/myapp/connection", we will get the following login.html template rendered −

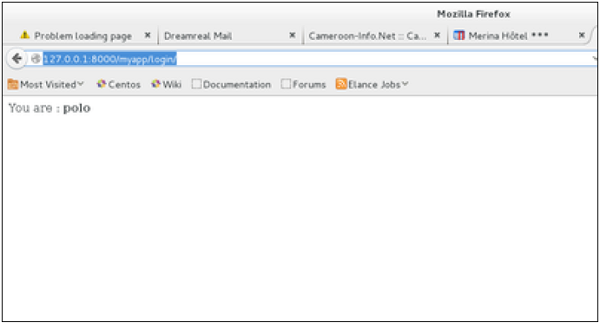

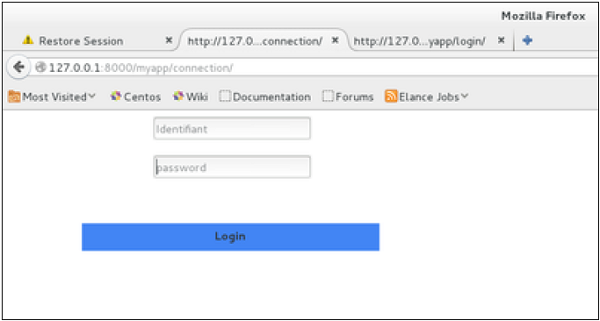

On the form post, the form is valid. In our case make sure to fill the two fields and you will get −

In case your username is polo, and you forgot the password. You will get the following message −

Using Our Own Form Validation

In the above example, when validating the form −

MyLoginForm.is_valid()

We only used Django self-form validation engine, in our case just making sure the fields are required. Now let’s try to make sure the user trying to login is present in our DB as Dreamreal entry. For this, change the myapp/forms.py to −

#-*- coding: utf-8 -*- from django import forms from myapp.models import Dreamreal class LoginForm(forms.Form): user = forms.CharField(max_length = 100) password = forms.CharField(widget = forms.PasswordInput()) def clean_message(self): username = self.cleaned_data.get("username") dbuser = Dreamreal.objects.filter(name = username) if not dbuser: raise forms.ValidationError("User does not exist in our db!") return username

Now, after calling the "is_valid" method, we will get the correct output, only if the user is in our database. If you want to check a field of your form, just add a method starting by "clean_" then your field name to your form class. Raising a forms.ValidationError is important.

File Uploading

It is generally useful for a web app to be able to upload files (profile picture, songs, pdf, words.....). Let's discuss how to upload files in this chapter.

Uploading an Image

Before starting to play with an image, make sure you have the Python Image Library (PIL) installed. Now to illustrate uploading an image, let's create a profile form, in our myapp/forms.py −

#-*- coding: utf-8 -*- from django import forms class ProfileForm(forms.Form): name = forms.CharField(max_length = 100) picture = forms.ImageFields()

As you can see, the main difference here is just the forms.ImageField. ImageField will make sure the uploaded file is an image. If not, the form validation will fail.

Now let's create a "Profile" model to save our uploaded profile. This is done in myapp/models.py −

from django.db import models class Profile(models.Model): name = models.CharField(max_length = 50) picture = models.ImageField(upload_to = 'pictures') class Meta: db_table = "profile"

As you can see for the model, the ImageField takes a compulsory argument: upload_to. This represents the place on the hard drive where your images will be saved. Note that the parameter will be added to the MEDIA_ROOT option defined in your settings.py file.

Now that we have the Form and the Model, let's create the view, in myapp/views.py −

#-*- coding: utf-8 -*- from myapp.forms import ProfileForm from myapp.models import Profile def SaveProfile(request): saved = False if request.method == "POST": #Get the posted form MyProfileForm = ProfileForm(request.POST, request.FILES) if MyProfileForm.is_valid(): profile = Profile() profile.name = MyProfileForm.cleaned_data["name"] profile.picture = MyProfileForm.cleaned_data["picture"] profile.save() saved = True else: MyProfileForm = Profileform() return render(request, 'saved.html', locals())

The part not to miss is, there is a change when creating a ProfileForm, we added a second parameters: request.FILES. If not passed the form validation will fail, giving a message that says the picture is empty.

Now, we just need the saved.html template and the profile.html template, for the form and the redirection page −

myapp/templates/saved.html −

<html> <body> {% if saved %} <strong>Your profile was saved.</strong> {% endif %} {% if not saved %} <strong>Your profile was not saved.</strong> {% endif %} </body> </html>

myapp/templates/profile.html −

<html> <body> <form name = "form" enctype = "multipart/form-data" action = "{% url "myapp.views.SaveProfile" %}" method = "POST" >{% csrf_token %} <div style = "max-width:470px;"> <center> <input type = "text" style = "margin-left:20%;" placeholder = "Name" name = "name" /> </center> </div> <br> <div style = "max-width:470px;"> <center> <input type = "file" style = "margin-left:20%;" placeholder = "Picture" name = "picture" /> </center> </div> <br> <div style = "max-width:470px;"> <center> <button style = "border:0px;background-color:#4285F4; margin-top:8%; height:35px; width:80%; margin-left:19%;" type = "submit" value = "Login" > <strong>Login</strong> </button> </center> </div> </form> </body> </html>

Next, we need our pair of URLs to get started: myapp/urls.py

from django.conf.urls import patterns, url from django.views.generic import TemplateView urlpatterns = patterns( 'myapp.views', url(r'^profile/',TemplateView.as_view( template_name = 'profile.html')), url(r'^saved/', 'SaveProfile', name = 'saved') )

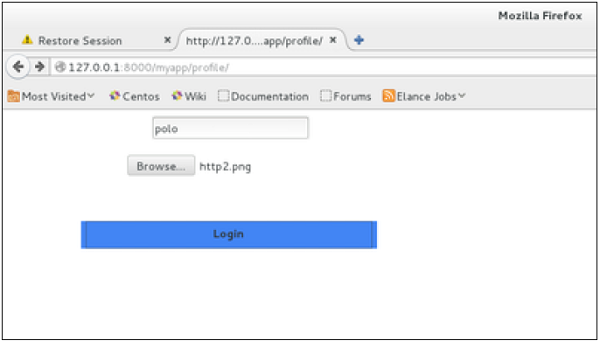

When accessing "/myapp/profile", we will get the following profile.html template rendered −

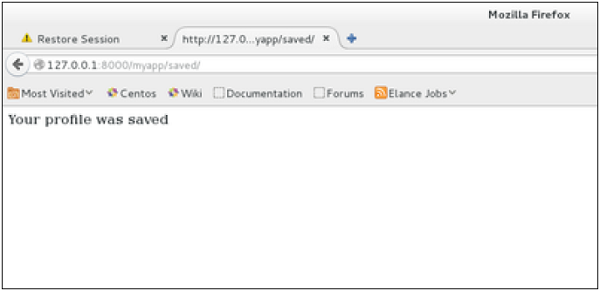

And on form post, the saved template will be rendered −

We have a sample for image, but if you want to upload another type of file, not just image, just replace the ImageField in both Model and Form with FileField.

Apache Setup

So far, in our examples, we have used the Django dev web server. But this server is just for testing and is not fit for production environment. Once in production, you need a real server like Apache, Nginx, etc. Let's discuss Apache in this chapter.

Serving Django applications via Apache is done by using mod_wsgi. So the first thing is to make sure you have Apache and mod_wsgi installed. Remember, when we created our project and we looked at the project structure, it looked like −

myproject/

manage.py

myproject/

__init__.py

settings.py

urls.py

wsgi.py

The wsgi.py file is the one taking care of the link between Django and Apache.

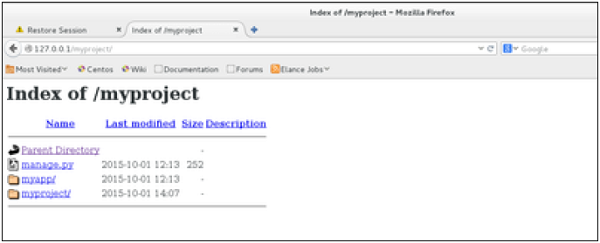

Let's say we want to share our project (myproject) with Apache. We just need to set Apache to access our folder. Assume we put our myproject folder in the default "/var/www/html". At this stage, accessing the project will be done via 127.0.0.1/myproject. This will result in Apache just listing the folder as shown in the following snapshot.

As seen, Apache is not handling Django stuff. For this to be taken care of, we need to configure Apache in httpd.conf. So open the httpd.conf and add the following line −

WSGIScriptAlias / /var/www/html/myproject/myproject/wsgi.py WSGIPythonPath /var/www/html/myproject/ <Directory /var/www/html/myproject/> <Files wsgi.py> Order deny,allow Allow from all </Files> </Directory>

If you can access the login page as 127.0.0.1/myapp/connection, you will get to see the following page −

Cookies Handling

Sometimes you might want to store some data on a per-site-visitor basis as per the requirements of your web application. Always keep in mind, that cookies are saved on the client side and depending on your client browser security level, setting cookies can at times work and at times might not.

To illustrate cookies handling in Django, let's create a system using the login system we created before. The system will keep you logged in for X minute of time, and beyond that time, you will be out of the app.

For this, you will need to set up two cookies, last_connection and username.

At first, let's change our login view to store our username and last_connection cookies −

from django.template import RequestContext def login(request): username = "not logged in" if request.method == "POST": #Get the posted form MyLoginForm = LoginForm(request.POST) if MyLoginForm.is_valid(): username = MyLoginForm.cleaned_data['username'] else: MyLoginForm = LoginForm() response = render_to_response(request, 'loggedin.html', {"username" : username}, context_instance = RequestContext(request)) response.set_cookie('last_connection', datetime.datetime.now()) response.set_cookie('username', datetime.datetime.now()) return response

As seen in the view above, setting cookie is done by the set_cookie method called on the response not the request, and also note that all cookies values are returned as string.

Let’s now create a formView for the login form, where we won’t display the form if cookie is set and is not older than 10 second −

def formView(request): if 'username' in request.COOKIES and 'last_connection' in request.COOKIES: username = request.COOKIES['username'] last_connection = request.COOKIES['last_connection'] last_connection_time = datetime.datetime.strptime(last_connection[:-7], "%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S") if (datetime.datetime.now() - last_connection_time).seconds < 10: return render(request, 'loggedin.html', {"username" : username}) else: return render(request, 'login.html', {}) else: return render(request, 'login.html', {})

As you can see in the formView above accessing the cookie you set, is done via the COOKIES attribute (dict) of the request.

Now let’s change the url.py file to change the URL so it pairs with our new view −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, url from django.views.generic import TemplateView urlpatterns = patterns('myapp.views', url(r'^connection/','formView', name = 'loginform'), url(r'^login/', 'login', name = 'login'))

When accessing /myapp/connection, you will get the following page −

And you will get redirected to the following screen on submit −

Now, if you try to access /myapp/connection again in the 10 seconds range, you will get redirected to the second screen directly. And if you access /myapp/connection again out of this range you will get the login form (screen 1)

Session

As discussed earlier, we can use client side cookies to store a lot of useful data for the web app. We have seen before that we can use client side cookies to store various data useful for our web app. This leads to lot of security holes depending on the importance of the data you want to save.

For security reasons, Django has a session framework for cookies handling. Sessions are used to abstract the receiving and sending of cookies, data is saved on server side (like in database), and the client side cookie just has a session ID for identification. Sessions are also useful to avoid cases where the user browser is set to ‘not accept’ cookies.

Setting Up Sessions

In Django, enabling session is done in your project settings.py, by adding some lines to the MIDDLEWARE_CLASSES and the INSTALLED_APPS options. This should be done while creating the project, but it's always good to know, so MIDDLEWARE_CLASSESshould have −

'django.contrib.sessions.middleware.SessionMiddleware'

And INSTALLED_APPS should have −

'django.contrib.sessions'

By default, Django saves session information in database (django_session table or collection), but you can configure the engine to store information using other ways like: in file or in cache.

When session is enabled, every request (first argument of any view in Django) has a session (dict) attribute.

Let's create a simple sample to see how to create and save sessions. We have built a simple login system before (see Django form processing chapter and Django Cookies Handling chapter). Let us save the username in a cookie so, if not signed out, when accessing our login page you won’t see the login form. Basically, let's make our login system we used in Django Cookies handling more secure, by saving cookies server side.

For this, first lets change our login view to save our username cookie server side −

def login(request): username = 'not logged in' if request.method == 'POST': MyLoginForm = LoginForm(request.POST) if MyLoginForm.is_valid(): username = MyLoginForm.cleaned_data['username'] request.session['username'] = username else: MyLoginForm = LoginForm() return render(request, 'loggedin.html', {"username" : username}

Then let us create formView view for the login form, where we won’t display the form if cookie is set −

def formView(request): if request.session.has_key('username'): username = request.session['username'] return render(request, 'loggedin.html', {"username" : username}) else: return render(request, 'login.html', {})

Now let us change the url.py file to change the url so it pairs with our new view −

from django.conf.urls import patterns, url from django.views.generic import TemplateView urlpatterns = patterns('myapp.views', url(r'^connection/','formView', name = 'loginform'), url(r'^login/', 'login', name = 'login'))

When accessing /myapp/connection, you will get to see the following page −

And you will get redirected to the following page −

Now if you try to access /myapp/connection again, you will get redirected to the second screen directly.

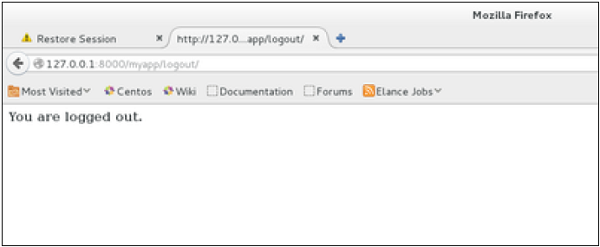

Let's create a simple logout view that erases our cookie.

def logout(request): try: del request.session['username'] except: pass return HttpResponse("<strong>You are logged out.</strong>")

And pair it with a logout URL in myapp/url.py

url(r'^logout/', 'logout', name = 'logout'),

Now, if you access /myapp/logout, you will get the following page −

If you access /myapp/connection again, you will get the login form (screen 1).

Some More Possible Actions Using Sessions

We have seen how to store and access a session, but it's good to know that the session attribute of the request have some other useful actions like −

-

set_expiry (value) − Sets the expiration time for the session.

-

get_expiry_age() − Returns the number of seconds until this session expires.

-

get_expiry_date() − Returns the date this session will expire.

-

clear_expired() − Removes expired sessions from the session store.

-

get_expire_at_browser_close() − Returns either True or False, depending on whether the user’s session cookies have expired when the user’s web browser is closed.

Caching

To cache something is to save the result of an expensive calculation, so that you don’t perform it the next time you need it. Following is a pseudo code that explains how caching works −

given a URL, try finding that page in the cache if the page is in the cache: return the cached page else: generate the page save the generated page in the cache (for next time) return the generated page

Django comes with its own caching system that lets you save your dynamic pages, to avoid calculating them again when needed. The good point in Django Cache framework is that you can cache −

- The output of a specific view.

- A part of a template.

- Your entire site.

To use cache in Django, first thing to do is to set up where the cache will stay. The cache framework offers different possibilities - cache can be saved in database, on file system or directly in memory. Setting is done in the settings.py file of your project.

Setting Up Cache in Database

Just add the following in the project settings.py file −

CACHES = { 'default': { 'BACKEND': 'django.core.cache.backends.db.DatabaseCache', 'LOCATION': 'my_table_name', } }

For this to work and to complete the setting, we need to create the cache table 'my_table_name'. For this, you need to do the following −

python manage.py createcachetable

Setting Up Cache in File System

Just add the following in the project settings.py file −

CACHES = { 'default': { 'BACKEND': 'django.core.cache.backends.filebased.FileBasedCache', 'LOCATION': '/var/tmp/django_cache', } }

Setting Up Cache in Memory

This is the most efficient way of caching, to use it you can use one of the following options depending on the Python binding library you choose for the memory cache −

CACHES = { 'default': { 'BACKEND': 'django.core.cache.backends.memcached.MemcachedCache', 'LOCATION': '127.0.0.1:11211', } }

Or

CACHES = { 'default': { 'BACKEND': 'django.core.cache.backends.memcached.MemcachedCache', 'LOCATION': 'unix:/tmp/memcached.sock', } }

Caching the Entire Site

The simplest way of using cache in Django is to cache the entire site. This is done by editing the MIDDLEWARE_CLASSES option in the project settings.py. The following need to be added to the option −

MIDDLEWARE_CLASSES += ( 'django.middleware.cache.UpdateCacheMiddleware', 'django.middleware.common.CommonMiddleware', 'django.middleware.cache.FetchFromCacheMiddleware', )

Note that the order is important here, Update should come before Fetch middleware.

Then in the same file, you need to set −

CACHE_MIDDLEWARE_ALIAS – The cache alias to use for storage. CACHE_MIDDLEWARE_SECONDS – The number of seconds each page should be cached.

Caching a View

If you don’t want to cache the entire site you can cache a specific view. This is done by using the cache_page decorator that comes with Django. Let us say we want to cache the result of the viewArticles view −

from django.views.decorators.cache import cache_page @cache_page(60 * 15) def viewArticles(request, year, month): text = "Displaying articles of : %s/%s"%(year, month) return HttpResponse(text)

As you can see cache_page takes the number of seconds you want the view result to be cached as parameter. In our example above, the result will be cached for 15 minutes.

Note − As we have seen before the above view was map to −

urlpatterns = patterns('myapp.views', url(r'^articles/(?P<month>\d{2})/(?P<year>\d{4})/', 'viewArticles', name = 'articles'),)

Since the URL is taking parameters, each different call will be cached separately. For example, request to /myapp/articles/02/2007 will be cached separately to /myapp/articles/03/2008.

Caching a view can also directly be done in the url.py file. Then the following has the same result as the above. Just edit your myapp/url.py file and change the related mapped URL (above) to be −

urlpatterns = patterns('myapp.views', url(r'^articles/(?P<month>\d{2})/(?P<year>\d{4})/', cache_page(60 * 15)('viewArticles'), name = 'articles'),)

And, of course, it's no longer needed in myapp/views.py.

Caching a Template Fragment

You can also cache parts of a template, this is done by using the cache tag. Let's take our hello.html template −

{% extends "main_template.html" %} {% block title %}My Hello Page{% endblock %} {% block content %} Hello World!!!<p>Today is {{today}}</p> We are {% if today.day == 1 %} the first day of month. {% elif today == 30 %} the last day of month. {% else %} I don't know. {%endif%} <p> {% for day in days_of_week %} {{day}} </p> {% endfor %} {% endblock %}

And to cache the content block, our template will become −

{% load cache %} {% extends "main_template.html" %} {% block title %}My Hello Page{% endblock %} {% cache 500 content %} {% block content %} Hello World!!!<p>Today is {{today}}</p> We are {% if today.day == 1 %} the first day of month. {% elif today == 30 %} the last day of month. {% else %} I don't know. {%endif%} <p> {% for day in days_of_week %} {{day}} </p> {% endfor %} {% endblock %} {% endcache %}

As you can see above, the cache tag will take 2 parameters − the time you want the block to be cached (in seconds) and the name to be given to the cache fragment.

Comments

Before starting, note that the Django Comments framework is deprecated, since the 1.5 version. Now you can use external feature for doing so, but if you still want to use it, it's still included in version 1.6 and 1.7. Starting version 1.8 it's absent but you can still get the code on a different GitHub account.

The comments framework makes it easy to attach comments to any model in your app.

To start using the Django comments framework −

Edit the project settings.py file and add 'django.contrib.sites', and 'django.contrib.comments', to INSTALLED_APPS option −

INSTALLED_APPS += ('django.contrib.sites', 'django.contrib.comments',)

Get the site id −

>>> from django.contrib.sites.models import Site >>> Site().save() >>> Site.objects.all()[0].id u'56194498e13823167dd43c64'

Set the id you get in the settings.py file −

SITE_ID = u'56194498e13823167dd43c64'

Sync db, to create all the comments table or collection −

python manage.py syncdb

Add the comment app’s URLs to your project’s urls.py −

from django.conf.urls import include url(r'^comments/', include('django.contrib.comments.urls')),

Now that we have the framework installed, let's change our hello templates to tracks comments on our Dreamreal model. We will list, save comments for a specific Dreamreal entry whose name will be passed as parameter to the /myapp/hello URL.

Dreamreal Model

class Dreamreal(models.Model): website = models.CharField(max_length = 50) mail = models.CharField(max_length = 50) name = models.CharField(max_length = 50) phonenumber = models.IntegerField() class Meta: db_table = "dreamreal"

hello view

def hello(request, Name): today = datetime.datetime.now().date() daysOfWeek = ['Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thu', 'Fri', 'Sat', 'Sun'] dreamreal = Dreamreal.objects.get(name = Name) return render(request, 'hello.html', locals())

hello.html template

{% extends "main_template.html" %} {% load comments %} {% block title %}My Hello Page{% endblock %} {% block content %} <p> Our Dreamreal Entry: <p><strong>Name :</strong> {{dreamreal.name}}</p> <p><strong>Website :</strong> {{dreamreal.website}}</p> <p><strong>Phone :</strong> {{dreamreal.phonenumber}}</p> <p><strong>Number of comments :<strong> {% get_comment_count for dreamreal as comment_count %} {{ comment_count }}</p> <p>List of comments :</p> {% render_comment_list for dreamreal %} </p> {% render_comment_form for dreamreal %} {% endblock %}

Finally the mapping URL to our hello view −

url(r'^hello/(?P<Name>\w+)/', 'hello', name = 'hello'),

Now,

-

In our template (hello.html), load the comments framework with − {% load comments %}

-

We get the number of comments for the Dreamreal object pass by the view − {% get_comment_count for dreamreal as comment_count %}

-

We get the list of comments for the objects − {% render_comment_list for dreamreal %}

-

We display the default comments form − {% render_comment_form for dreamreal %}

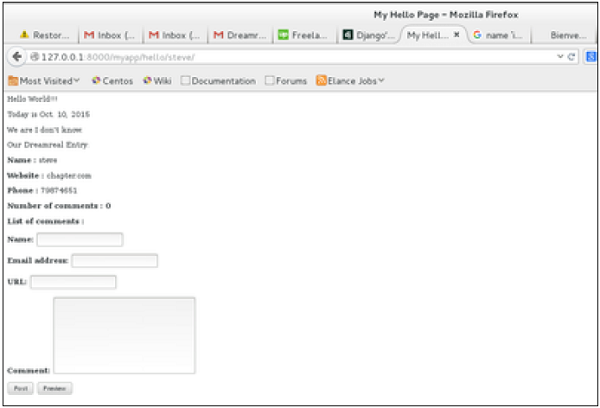

When accessing /myapp/hello/steve you will get the comments info for the Dreamreal entry whose name is Steve. Accessing that URL will get you −

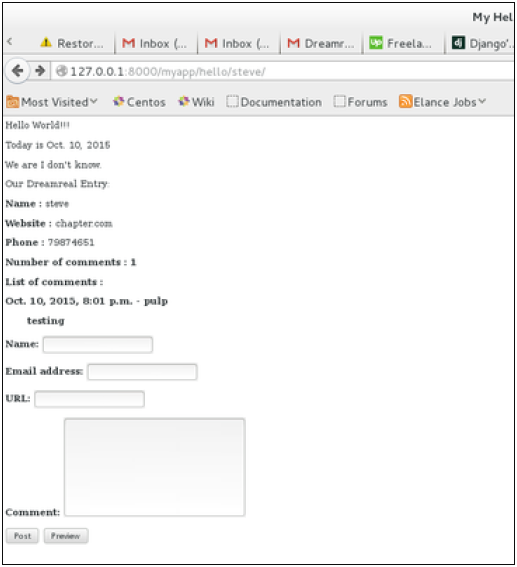

On posting a comment, you will get redirected to the following page −

If you go to /myapp/hello/steve again, you will get to see the following page −

As you can see, the number of comments is 1 now and you have the comment under the list of comments line.

RSS

Django comes with a syndication feed generating framework. With it you can create RSS or Atom feeds just by subclassing django.contrib.syndication.views.Feed class.

Let's create a feed for the latest comments done on the app (Also see Django - Comments Framework chapter). For this, let's create a myapp/feeds.py and define our feed (You can put your feeds classes anywhere you want in your code structure).

from django.contrib.syndication.views import Feed from django.contrib.comments import Comment from django.core.urlresolvers import reverse class DreamrealCommentsFeed(Feed): title = "Dreamreal's comments" link = "/drcomments/" description = "Updates on new comments on Dreamreal entry." def items(self): return Comment.objects.all().order_by("-submit_date")[:5] def item_title(self, item): return item.user_name def item_description(self, item): return item.comment def item_link(self, item): return reverse('comment', kwargs = {'object_pk':item.pk})

-

In our feed class, title, link, and description attributes correspond to the standard RSS <title>, <link> and <description> elements.

-

The items method, return the elements that should go in the feed as item element. In our case the last five comments.

-

The item_title method, will get what will go as title for our feed item. In our case the title, will be the user name.

-

The item_description method, will get what will go as description for our feed item. In our case the comment itself.

-

The item_link method will build the link to the full item. In our case it will get you to the comment.

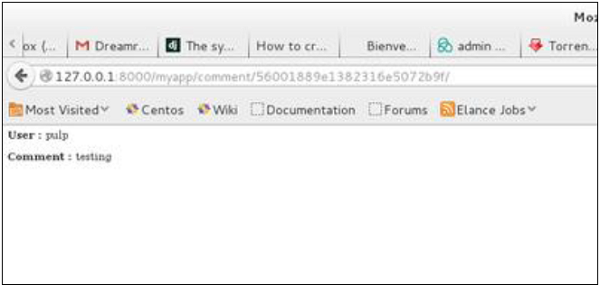

Now that we have our feed, let's add a comment view in views.py to display our comment −

from django.contrib.comments import Comment def comment(request, object_pk): mycomment = Comment.objects.get(object_pk = object_pk) text = '<strong>User :</strong> %s <p>'%mycomment.user_name</p> text += '<strong>Comment :</strong> %s <p>'%mycomment.comment</p> return HttpResponse(text)

We also need some URLs in our myapp urls.py for mapping −

from myapp.feeds import DreamrealCommentsFeed from django.conf.urls import patterns, url urlpatterns += patterns('', url(r'^latest/comments/', DreamrealCommentsFeed()), url(r'^comment/(?P\w+)/', 'comment', name = 'comment'), )

When accessing /myapp/latest/comments/ you will get our feed −

Then clicking on one of the usernames will get you to: /myapp/comment/comment_id as defined in our comment view before and you will get −

Thus, defining a RSS feed is just a matter of sub-classing the Feed class and making sure the URLs (one for accessing the feed and one for accessing the feed elements) are defined. Just as comment, this can be attached to any model in your app.

AJAX

Ajax essentially is a combination of technologies that are integrated together to reduce the number of page loads. We generally use Ajax to ease end-user experience. Using Ajax in Django can be done by directly using an Ajax library like JQuery or others. Let's say you want to use JQuery, then you need to download and serve the library on your server through Apache or others. Then use it in your template, just like you might do while developing any Ajax-based application.

Another way of using Ajax in Django is to use the Django Ajax framework. The most commonly used is django-dajax which is a powerful tool to easily and super-quickly develop asynchronous presentation logic in web applications, using Python and almost no JavaScript source code. It supports four of the most popular Ajax frameworks: Prototype, jQuery, Dojo and MooTools.

Using Django-dajax

First thing to do is to install django-dajax. This can be done using easy_install or pip −

$ pip install django_dajax $ easy_install django_dajax

This will automatically install django-dajaxice, required by django-dajax. We then need to configure both dajax and dajaxice.

Add dajax and dajaxice in your project settings.py in INSTALLED_APPS option −

INSTALLED_APPS += ( 'dajaxice', 'dajax' )

Make sure in the same settings.py file, you have the following −

TEMPLATE_LOADERS = ( 'django.template.loaders.filesystem.Loader', 'django.template.loaders.app_directories.Loader', 'django.template.loaders.eggs.Loader', ) TEMPLATE_CONTEXT_PROCESSORS = ( 'django.contrib.auth.context_processors.auth', 'django.core.context_processors.debug', 'django.core.context_processors.i18n', 'django.core.context_processors.media', 'django.core.context_processors.static', 'django.core.context_processors.request', 'django.contrib.messages.context_processors.messages' ) STATICFILES_FINDERS = ( 'django.contrib.staticfiles.finders.FileSystemFinder', 'django.contrib.staticfiles.finders.AppDirectoriesFinder', 'dajaxice.finders.DajaxiceFinder', ) DAJAXICE_MEDIA_PREFIX = 'dajaxice'

Now go to the myapp/url.py file and make sure you have the following to set dajax URLs and to load dajax statics js files −

from dajaxice.core import dajaxice_autodiscover, dajaxice_config from django.contrib.staticfiles.urls import staticfiles_urlpatterns from django.conf import settings Then dajax urls: urlpatterns += patterns('', url(r'^%s/' % settings.DAJAXICE_MEDIA_PREFIX, include('dajaxice.urls')),) urlpatterns += staticfiles_urlpatterns()

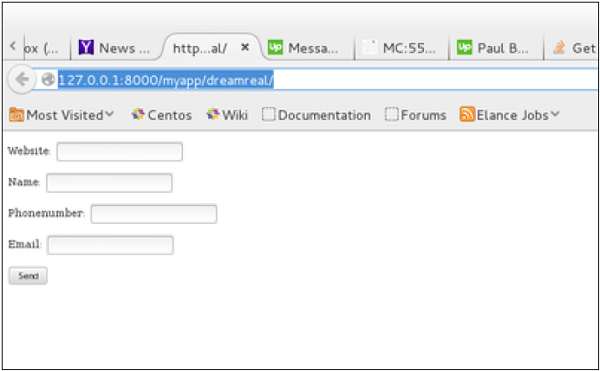

Let us create a simple form based on our Dreamreal model to store it, using Ajax (means no refresh).

At first, we need our Dreamreal form in myapp/form.py.

class DreamrealForm(forms.Form): website = forms.CharField(max_length = 100) name = forms.CharField(max_length = 100) phonenumber = forms.CharField(max_length = 50) email = forms.CharField(max_length = 100)

Then we need an ajax.py file in our application: myapp/ajax.py. That's where is our logic, that's where we put the function that will be saving our form then return the popup −

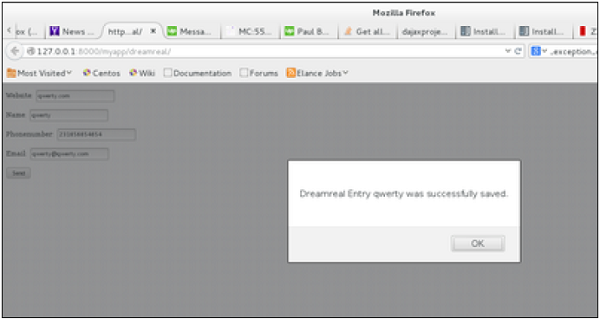

from dajaxice.utils import deserialize_form from myapp.form import DreamrealForm from dajax.core import Dajax from myapp.models import Dreamreal @dajaxice_register def send_form(request, form): dajax = Dajax() form = DreamrealForm(deserialize_form(form)) if form.is_valid(): dajax.remove_css_class('#my_form input', 'error') dr = Dreamreal() dr.website = form.cleaned_data.get('website') dr.name = form.cleaned_data.get('name') dr.phonenumber = form.cleaned_data.get('phonenumber') dr.save() dajax.alert("Dreamreal Entry %s was successfully saved." % form.cleaned_data.get('name')) else: dajax.remove_css_class('#my_form input', 'error') for error in form.errors: dajax.add_css_class('#id_%s' % error, 'error') return dajax.json()

Now let's create the dreamreal.html template, which has our form −

<html> <head></head> <body> <form action = "" method = "post" id = "my_form" accept-charset = "utf-8"> {{ form.as_p }} <p><input type = "button" value = "Send" onclick = "send_form();"></p> </form> </body> </html>